The crisis still unfolding at Japan’s devastated Fukushima Daiichi nuclear reactors will have a huge impact on the global nuclear industry. That will not only be in terms of the running of existing reactors and the design and location of future ones, but also in the reevaluation of nuclear’s place in energy policies.

Europe has already started that process. Germany is shutting down reactors; Spain, Russia and the U.K. are ordering safety reviews. China has now followed the U.S. in suspending the approval process for new nuclear power stations so that safety standards can be reexamined. Beijing has also said it will revise its standards for the safety management of nuclear plants without giving any detail about what those revisions might entail.

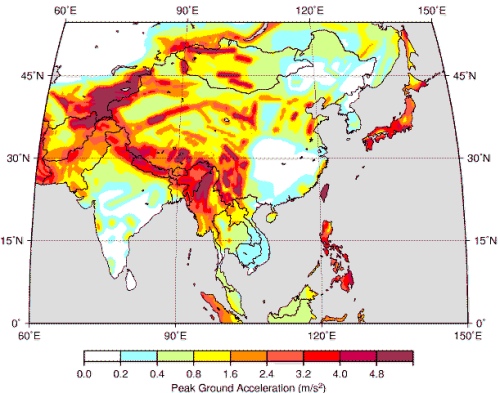

Fukushima is unlike Chernobyl or even Three Mile Island in that the damage was caused by a natural disaster, whereas the other two were to varying degrees a result of human error. But seismic risks, including tsunamis, are highly relevant in many parts of the world with expanding nuclear programs to satisfy growing energy needs such as southeastern Europe, India, Iran, Turkey, the U.S. and, of course, China, which accounts for 40% of the world’s nuclear power plants currently under construction. This Asian slice of a U.N.-sponsored seismic risk map, below, shows the most hazardous areas, in the dark red.

Caixin has a map of where China’s existing and planned nuclear power plants are here which you can easily overlay in your mind on the map above, while The Wall Street Journal has a map plotting them against China’s fault lines here.

Beijing has already said it doesn’t plan to alter its plans to build new reactors. The new five-year plan proposes a fourfold expansion of the country’s nuclear power generation capacity from 10 gigawatts (less than 2% of the country’s current electricity generation) to 40 gigawatts. Last year Beijing approved 34 new nuclear power plants to add 37 gigawatts of capacity. Work has started on 26 six of those units, accounting for 78% of the planned new capacity. The newly announced safety review is likely to mean no more than a pause for breath.

Liu Tienan, chief of China’s National Energy Bureau, does say that China has much to learn from Japan’s crisis, particularly about safety. Modern reactors, so called Generation 3 reactors, are more safely designed than Generation 1 and 2 reactors, the type in use at Fukushima. Generation 3 reactors use a passive cooling system that does not require electricity to run. They may well have survived the Sendai earthquake and tsunami in tact. It was the loss of electric power needed to run the cooling system and its back-ups that put the reactors at risk, not the direct impact of the quake and tsunami. That said plenty of wars have been lost by generals refighting the last one.

China is pursuing home-grown nuclear power generation technology based on what it is transferring from American, French and Japanese nuclear companies (no one really knows what is going on in China’s military nuclear program). On the civilian side, the AP1000 reactors Beijing has chosen for construction on the east coast and plans to build further inland are a Generation III design. They are also being used for 14 proposed reactors in the U.S. The design has been approved by the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission, but there remain some concerns about its safety, particularly its capacity to survive being hit by an aircraft.

No power generation system will ever be 100% safe. When nuclear goes wrong, it tends to go catastrophically wrong. Predicting what could trigger that catastrophe will never be a 100% science, either. In 2003, the Japanese Nuclear Commission was set this safety target:

The mean value of acute fatality risk by radiation exposure resultant from an accident of a nuclear installation to individuals of the public, who live in the vicinity of the site boundary of the nuclear installation, should not exceed the probability of about 1×10^6 per year.

1×10^6 is a million. Japan’s once-in-a-million-years event happened just eight years later.

China’s nuclear program has had its safety issues in the past, and Fukushima will give more strength to the voices raising concerns about nuclear safety. But the country’s need to generate ever more power to fuel growth and to meet a self-imposed goal of generating 15% of its energy needs using non-fossil fuels by 2020 means it is unlikely to scale back its nuclear program, even if it slows the pace of development. Beijing can convince itself that the safety issues can be handled (even if convincing its citizens is another matter, and that may depend on how Fukushima turns out). Its biggest impediment is, as it is everywhere for nuclear, cost. Reactors are expensive to build and have histories of expensive project delays. The country is looking at a potential bill of $150 billion over the next decade for its nuclear program, more if the safety review imposes additional safety-related costs. Meanwhile, there are less expensive alternatives, such as gas, and in future renewables developing rapidly. The future pace of the development of China’s nuclear energy program won’t be decided on safety alone.

The momentum of the 12th five year plan makes it hard for china to change it’s energy policy.

3D GeoSEIS model of tectonic structure of geologic-geophysical environment of Fukushima nuclear power plant: http://www.flickr.com/photos/jeisus2012/5541801626/

This created 3D GeoSEIS model has mapped volumetric structure of a strains field which is related with subduction an oceanic plate in the western and southern directions.

The 3D GeoSEIS Model proves, that the nuclear station has been constructed in very adverse tectonic structure which increments destructive energy of the earthquakes and tsunami.

3D-4D GeoSEIS models should be created before construction of objects dangerous for people!

Pingback: China Cracks On With Nuclear Power Plant Construction | China Bystander

Pingback: China’s Nuclear-Power Safety Review: An Update | China Bystander

I believe China is moving in the right direction when it comes to powering it’s economy.

Production is related to building manufacturing that will be heavily need for there people.

I see there need for more experienced business opportunities to plan for the what if’s.

Other wise do more and slow on coal usage all of our health depends on China’s insight into the

future.